Sean Devine‘s play Re: Union tells the story of Emily Morrison’s confrontation with Robert McNamara, the United States Secretary of Defense during the Vietnam War. The story is fraught with tensions both personal and political — it raises questions about effective protest, ethics, morality, government and the mechanisms of war — questions that still resound within me, important and unsettled — days after seeing the play. Re:Union’s is a co-production of Pacific Theatre and Horseshoes & Handgrenades, and had its world premiere at Pacific Theatre last Friday.

The play is set in Anthrax-phobic Washington D.C. around the time George Bush Jr announced the country’s invasion of Iraq — an invasion much like that of Vietnam, in that it continues despite public dissent, has been immensely costly, and has little to gain and much more to lose from what seems like a futile endeavor. In this political climate, Emily Morrison travels to the capital because she must have audience with McNamara, as she has something important to say.

Some history about the characters is in order. Emily Morrison is the daughter of ethics professor Norman Morrison, a pacifist who protested American involvement in the Vietnam war by soaking himself in kerosene and setting himself on fire outside Robert McNamara’s Pentagon office. For reasons that historians (or the audience at the end of Re:Union) cannot entirely ascertain, Morrison took his daughter Emily with him that day in 1965, when she was not-yet a year old. Norman Morrison set himself on fire to express how strongly he felt the pain of those suffering in Vietnam — a costly, symbolic act, that did not persuade Robert McNamara to try and stop the war.

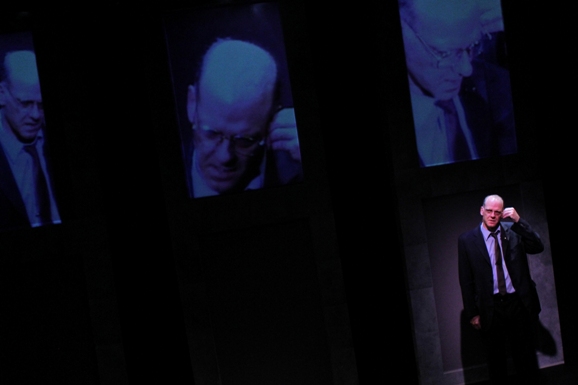

While it would be simple to conclude with resignation that Robert McNamara was a soulless, amoral warmonger with no concern for the suffering of others, Re:Union‘s portrayal of McNamara makes such a reduction impossible (though it does entertain the notion substantially). Through his interaction with the intrepid Emily Morrison, the play shows McNamara as someone underneath whose gruff, defensive demeanor is a sensitive, intelligent man who is conflicted by his past, and even present, actions. Though in the play McNamara never directly states his regrets about Vietnam, Andrew Wheeler’s subtle and powerful portrayal of this historical figure hints at the immense weight of guilt McNamara still carries with him. All the while his position remains complicated by his loyalty to the American state, or his fear of denouncing current government actions.

Errol Morris famously interviews McNamara in the documentary The Fog of War, where the retired Secretary of Defense describes himself as a war criminal, publicly acknowledging the impact of his decisions while providing fascinating insight into the historical moment of America in the 1960s. I re-watched this documentary after watching Re:Union, and I got so much more out of it than the first time I watched it. McNamara takes centre stage in this documentary, while the story of Norman Morrison appears as a tragic coda, and the story of Emily is hardly seen at all.

In refreshing contrast, Emily Morrison (played by Alexa Devine) is a strong voice in Re:Union: she takes her moral and political convictions to butt heads with McNamara’s radically different ones, and in the ensuing exchange they raise questions about political action. Most strident are the questions: what are the consequences of action? and what are the consequences of inaction? For me the play sparked an invigorating debate about Norman Morrison’s radical act of protest — while it displayed an immense level of devotion to peace, would another expression of dissent have been more effective in halting the war? Were the decision-makers in a position to be so moved? What is an effective protest? What can individuals do in the face of the mechanized war effort (the same Eisenhower warned us of in his farewell address)? How can the individual influence the state? Could Morrison’s act in any way be construed as selfish? The Robert McNamara in the play certainly believes it was, while Emily vehemently disagrees, and follows in her father’s footsteps. . . Frequent and ghostly visitations from Norman Morrison (played by Evan Frayne), as the professor of ethics addressing his class, flesh out the philosophical background required to understand his line of thinking, while the grief of all three morally fraught characters endures throughout the performance.

Re:Union does an exquisite job of evoking the environments of a rainy D.C., Morrison’s lonely, seedy motel, Morrison’s university lecture hall, an underground subway, the invisible crowds and sense of expectation at McNamara’s press conferences, and the darkened courtyard outside McNamara’s office in the Pentagon. It does all this in the intimate Pacific Theatre with ingeniously few and simple props, skilled lighting and projection design, and the cleverness of many more talents which I have not yet the know-how to name, but will do my best to credit: a big congratulations production designer Jason H. Thompson, director John Langs, sound designer Noah Drew, and set and lighting designer John Webber for drawing a variety of chilling and convincing environments out of the theatre space, and with such seamless transitions between scenes. Thank you to actors Alexa Devine, Andrew Wheeler and Norman Morrison for their moving performances and to Sean Devine for writing this thought-provoking play.

You can see Sean Devine’s Re:Union at the Pacific Theatre until November 12. Showtimes are Wednesday — Saturday at 8 p.m., with Saturday matinees at 2 p.m.

On a related note, alongside Re:Union the co-production company Horseshoes & Handgrenades is offering a community outreach series about political activism, community responsibility and anti-militarism called The Activist City. Offerings include panel discussions, workshops, poetry readings, guest speakers and bloggers. Many of these discussions are by-donation, and sound pretty interesting. Check out The Activist City schedule to find what you’d like to attend!

Leave a Reply