Earlier in March the First World War claimed two more lives in Belgium, when untouched explosives were uncovered at a building site in Ypres. In a month it will have been one hundred years since some Austrian archduke was assassinated, precipitating the greatest threat to western imperialism and civilization in human history – the Great War. Unlike every November 11th, July 28th is a different kind of remembrance, one where we should contemplate the world that was irrevocably created from the First World War, and all the aspirations and shortcomings for peace since.

We live in a world that failed to transcend war, as was so hopefully lobbied for by peace advocates after the “Great War for Civilization” in the idea of an international league for world peace. Humankind, at the height of globalization – when nearly the entire planet was under the command of a few colonial empires – missed its best chance at a permanent, enforced, peace. Instead we went on to fight yet another catastrophic war which could have – even worse than miss an opportunity – forever encase global politics in the totalitarian control of fascism and the draining fight against it. We avoided that world by the luck and total determination of the Allies of the Second World War, but by then the liberal moment had passed. The alternative liberal-capitalist solution to generalized modern warfare was now discredited, with much of the planet now embracing the communist version of history; that the convulsions of capitalism and imperial power politics guaranteed cyclical warfare and destitution, and that only post-capitalist societies, in fraternal arms, could save the world from destruction.

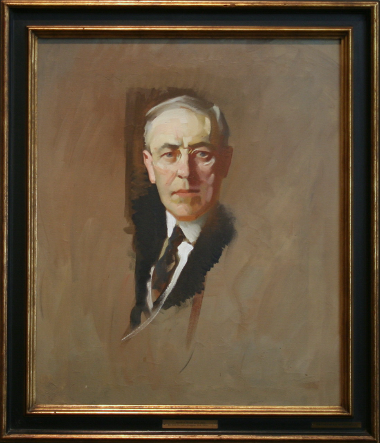

There was a period of history, brief but absolutely essential to remember, when across the political spectrum most believed world peace was possible, and the primary political differences between people were the means by which such peace would be achieved. An illustrative example was the opposition in the United States Senate to joining Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations. Roosevelt, Taft, and many members of the Senate, whom were Wilson’s opposition, were positively and vocally in favour of a league of countries to prevent future wars. During the First World War, the League to Enforce Peace, a civilian pro-league organization, advocated for an international body of judges, appointed by the world’s countries, to write, codify and adjudicate international law. This vision was entirely unlike the eventual League of Nations – which was a body of diplomats negotiating disputes – and though this was only one factor, we should remember that the ideological clash between different ideas of internationalism was the salient impetus for opposition to Wilson’s league, not pure realism (a term and conceptual framework which only gained prominence in the 1940s) about liberal institutionalism.

This was an historical moment when serious people in politics believed war should be outlawed in all its forms – that no aggression could ever be perpetrated, even with international agreement (just read the introduction online to Salmon Levinson 1921 book, Outlawry of War). To some adherents of this belief, despite having the same objective of world peace, creating the League of Nations (or one could suppose the United Nations today) was not the right course of action because it was an alliance – and alliances could sanction some wars as legal. There was once a time when most popular sentiment was internationalist, and many people believed world peace could be achieved in their lifetime.

The remainder of the twentieth century would only be saved from another final conflict by an arms race so terrifying even the most belligerent men among the leadership of the United States and the Soviet Union couldn’t commit to the costs – in other words, it took humanity the viscerally upfront possibility of actual (and imminent) annihilation to bring about a semblance of peace in the modern era. No rapid escalation of small squabbles into intercontinental war; only the insane could possibly argue for fighting out the differences; thank the bomb.

In 2014, there are still nuclear weapons wielding states, multiple of which are in competition for parts of the planet, whether the Korean peninsula, the contested Kashmir region of South Asia, the sacred soil of Islam, the lands of the Jews, or Crimea. The borders of weaker states are still up to the power politics of larger countries and the permanent members of the United Nations; this article comes out as Crimea’s status is the subject of economic warfare between the west and Russia.

We should therefore all take a moment’s resignation, and come to respect the fragility of the world’s relative peace – it’s the product of a similar imperial competition the eighteenth century Great Powers were unabashedly engaging each other in for the benefit of “civilization.” We don’t live in a world where global peace is an achievable goal, but a world which only accepted the sheer horror of conflict between the Great Powers as a sufficient reason to minimize war. It is this less than satisfactory truth that July 28th means to me – the other remembrance day.

Hiten Vyas says

Hi Felix,

Excellent article, indeed.

I wasn’t aware of the previous efforts to bring a total end to wars and it was interesting to learn about them.

Thank you.

Emme Rogers says

Thanks Hiten! I know I always love to debate with Felix on such topics. He is a very well read young man!